Modern slavery and supply chains

August 17, 2020

Good economics vs. bad liberals

I took some time out from college and worked for a lawyer in Oakland who focused on housing issues. Once he had me document the living conditions in one of the downtown SROs (Single Room Occupancy “hotels” - buildings that rented rooms to families 29 days at a time so they wouldn’t get renters rights). I returned with some truly horrific pictures - roofs caved in, rats, etc… I thought I’d nailed the assignment, so I was disappointed that the lawyer wasn’t as excited. He explained to me that if the pictures were too horrific, the SRO would be condemned - and the renters would be homeless, which is (arguably) worse for them. So we needed pictures that were bad enough to sue for change, but not bad enough to make things worse.

So I was curious when I saw that Tyler Cowen made a similar argument in Bloomberg about the “Slave-Free Business Certification Act of 2020” introduced in the senate by Josh Hawley.

Such a get-tough approach has a superficial appeal. Yet placing an investigative burden on companies may not lead to better outcomes.

Consider the hypothetical case of a U.S. retailer buying a shipment of seafood routed through Vietnam. It fears that some of the seafood may have come from Thailand, where there are credible reports of (temporary) slavery in the supply chain. How does it find out if those reports are true? Asking its Vietnamese business partner, who may not even know the truth and might be reluctant to say if it did, is unlikely to resolve matters.

It is unlikely that businesses, even larger and profitable ones, will be in a position to hire teams of investigative journalists for their international inputs. Either they will ignore the law, or they will stop dealing with poorer and less transparent countries. So rather than buying shrimp from Southeast Asia, that retailer might place an order for more salmon from Norway, where it is quite sure there is no slavery going on.

The result, according to Cowen, is likely to be increased slavery higher prices for consumers and increased slavery. The former is seemingly obvious (buying goods not produced by slaves will be more expensive), but the latter requires some explanation. Supply chains will source from richer countries where it is easier to be certain that the labor isn’t coerced. The result - (again, according to Cowen) - less money flowing into poorer countries, more poverty, ergo more slavery.

Is this really good economics?

There’s a certain swagger about economists that is quite attractive - I think it’s a combination of counter-intuitiveness and certainty. And Cowen certainly has the swagger when he says that this bill is the wrong way to address the problem of slavery. Instead, he suggests that governments do the regulation bit, and let opaque supply chains do what they do.

Now there is a fair bit of truth to the concern that companies are risk averse and would rather not do business than take on some risks. In Poor Economics Bannerjee and Duflo describe cases where because of reputation risks there might be no price at which a company will order say t-shirts or carpets from a new vendor or region of a country, and the developing country is indeed the worse for it. So it’s worth thinking about.

Underlying Cowen’s argument lie two models - the first is slavery is directly correlated to poverty, and the second is that it is independent of the supply chain. Neither of these is entirely true. Slavery is not simply the lowest end payment for labor. It requires the presence of a “slaver” - someone who is paid to coerce labor. People aren’t going to be slavers unless there is demand for slavery. Which brings us to the supply chain.

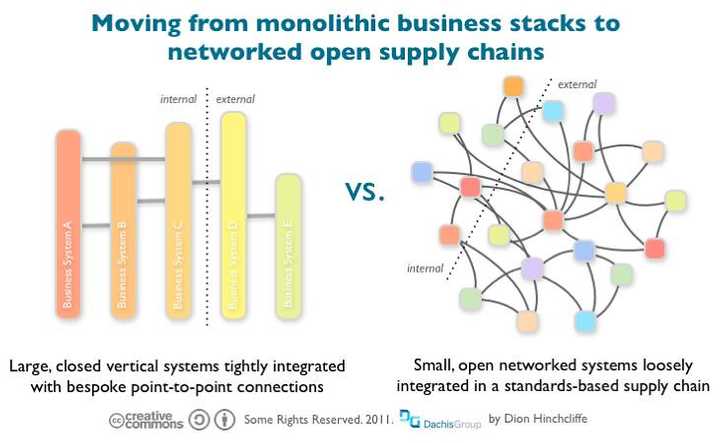

There is a lot of marketing in the supply chain world, about dynamism and openness, but for all the stories about being able to buy your chips (shrimp or silicon) from Vietnam when Thailand is in crisis there is the fact that this almost never happens and it certainly isn’t the reason behind the design of the supply chain. Typically there is just one driver for the design. Let’s take fast fashion, for example.

The fast fashion supply chain

The consumer wants something “fresh” and “new” - something he’s never seen before. If he does like it, he’s going to tell all his friends, who will want it right away. If they don’t get it right away, they will move on to something else. If he doesn’t like it, no one will want it. It needs to be cheap - at least as cheap as a “standard” item, and (obviously) the consumer isn’t going to pre-pay for the privilege of trying something new.

So what do you do as a business that is supplying fast fashion? HBR tells you to align incentives and this is what you try to do. You only pay for goods 60-90 days after you receive them. You implicitly (or explicitly!) promise to pay for goods but cancel orders when it turns out a style isn’t selling. You don’t build a relationship with a particular kind of shop with a particular kind of expertise, because every design requires a different kind of expertise. Instead you build relationships with brokers who will find the right kind of shops for you.

What does the broker do? The business has put them on the hook for the goods, so they need to find manufacturers who will make clothes and take on the fabric and labor cost at the risk of not getting paid. If the deal works out, they will get paid a handsomely. However, they have to protect themselves because they likely will get paid late, and quite possibly will not get paid at all. So - what is the magic that allows this risk to be pushed further down the supply chain on to the laborer? How do you get someone to work and not get paid until the consumer pays the corporation who pays the broker etc, etc? In some fashion, the result is going to be very unfair to the person picking up the tab for the benefit that the consumer wants.

The seafood supply risk profile is similar. You outfit a boat, provide fuel, feed a crew, but you’re at the mercy of the oceans in terms of your catch. You don’t get paid at the very least till you deliver your catch and possibly till your customers customers pay for their shrimp.

This sort of risk profile - where someone in the supply chain has a (relatively) massive reward in the future but significant incentives to lower labor cost now - that is pretty much ensuring that the someone will be at best running a terrible workplace, and at worst enslaving people.

In my model (and to be clear, just like Cowen’s argument, this is a model) while poverty sets the stage for slavery, the proximate cause of the slavery is the supply chain. In fact, this sort of “regulatory arbitrage” is precisely why the supply chain exists and why it is so opaque. Tyler Cowen needs to ask why the retailer is buying seafood “routed through Vietnam” when it originates in Thailand.

The problem is us

If the supply chain causes the problem then it makes sense to focus on it to solve the problem. But the problem isn’t entirely the supply chain - the supply chain is simply designed to deliver what consumers want. If we modify the supply chain to ensure that it is slavery free we will likely see not just higher costs but also lower choice for consumers. Fast fashion might be a bit less fast or a bit less fashionable, as businesses like H&M and Zara become less nimble.

But what about the poor in developing countries? Will there in fact be more slaves as a result of requiring audits for supply chains? They will likely be somewhat poorer, because some businesses will choose to not work with poorer countries. But my model does not equate this with an increase in slavery - rather, because in my model supply chains drive slavery by the incentives they create for slavers, regulating the supply chain will in fact reduce slavery.

What about Tyler Cowen’s other solutions?

Tyler Cowen proposes two other approaches to solving the problem. One is consumer activism, the other government regulation. Government regulation is precisely the problem that the opacity of the supply chain is intended to solve. If the government targets slavery in China, the supply chain can move to slaves in India.

Consumers on the other hand face a collective action problem - if everyone is going to pay for slave-free stuff, I’m in - but if I’m the only one and it’s not exactly clear that these clothes were made by slaves, then… I’ll take my cheap t-shirts, thanks. That’s exactly the kind of thing that government regulation was intended to solve.

So what’s not to love about the act?

On the one hand the audit-industrial complex is definitely an effective way force some change across american business. On the other hand, while it’s effective, while working in Finance I’ve seen how inefficient it is as lever. But that’s a subject for a different blog post…